Cementing is one of the most critical steps in well completion. Sadly, coming at the end of drilling and in the haste to put a well on production, rarely is the time and commitment taken to get a good job. We then spend significantly more time correcting it or battling the effects of a bad cement job. Cement fills and seals the annulus between the casing string and the drilled hole. It has three general purposes:

(1) zone isolation and segregation,

(2) corrosion control, and

(3) formation stability and pipe strength improvement.

Cement forms an extremely strong, nearly impermeable seal from a thin slurry. The properties of the cement slurry and its behavior depends on the components and the additives in the cement slurry. This chapter will focus on the basics of the cementing process. For further information on cement and the cementing process the reader is referred to the Society of Petroleum Engineering’s Cementing Monograph.’

Most cements used in the oil industry are a type of portland cement. The name portland was taken from an English channel island with a limestone quarry that was used as source of stone for the development of portland cement. Portland cement is produced from limestone and either clay or shale by roasting at 2600 to 3000°F. The high temperature fuses the mixture into a material called clinker cement.’ After the roasting step, the rough clinker product is ground to a size specified by the grade of the cement. The final size of the cement particles has a direct relationship with how much water is required to make a slurry without producing an excess of water at the top of the cement or in pockets as the cement hardens. The crystals seen in set cement include:’ C3S - tricalcium silicate, C2S - dicalcium silicate, C4AF - tetracalcium aluminoferrite, C3A - tricalcium aluminate, MgO - periclase or magnesium oxide, and CaO - free lime. Not all cements, even those made from the same components, will react in the same manner when mixed with water. Basically, the differences are in the fineness of the grind of the cement, impurities in the water and in some minor additives added during the cement manufacturing process. Figure 3.1 gives the API designated classes for cements. These classifications of cement were in response to deeper and hotter downhole conditions. Note that the useful depths given in the data are derived from average pumping times of neat (no additives) cement for average temperatures involved at these depths. Actual well environment controls the limits of the cement. Also, additives such as accelerators and retarders can be used to modify the behavior of the cement. In this manner, a class H cement, for example, can be used to much greater depths than the 8000 ft limit seen in the table.

Figure 3.1: API Cement Classes

There are a number of other cements that do not fall specifically into any general classification. These cements are special blends of portland and additives or cements based on other chemistry. They include pozzlin cement, which incorporates organic resin technology, expanding cements, which increase in volume as the cement sets, silica and lime cement for hot wells, and low heat generating cements for permafrost applications. These cements are rarely used in general completions because they are more expensive than portland or have other traits that are less desirable than those of portland.

Environmental conditions and available completion equipment may significantly affect the performance of the cement or place special requirements on the cement. The unique problems of the effect of temperature on cement setting and long-term strength of cements have led to development of special cements for both steam wells and those in arctic environments. High temperatures sharply reduce cement strength and durability, necessitating the development of stabilizers. Silica additives and lime based cements have proved effective in thermal wells. Permafrost cement was developed in response to a need to cement formations to depths of 2000 ft without producing sufficient heat of hydration from

setting the cement to melt and destabilize the permafrost. The most important aspect of cementing blending is obtaining a consistent slurry with the proper amount of additives and mix water. The optimum water-to-cement ratio for a cement slurry is a compromise.

Maximum cement strength occurs at a water-to-cement ratio of about 2.8 galhack. This is

the minimum amount of water necessary to fully hydrate and chemically react with the cement ground to a size that represents Class G. But, a slurry mixed at this water rate has a very high viscosity and cannot be pumped. If too much water is used to aid in pumping and displacement, low strength and a very high free water quantity will occur. The tradeoff between cement strength and the mixing water volume is seen in the data of Figure 3.2.* Free water is defined as water that is not needed by the cement for reaction. When flow stops, it separates out to the top of the cement column. Separation may occur at the top of a long column or in pockets in highly deviated w e k 3 These pockets contribute to annular gas leakage and other annular flow problems. Cement is mixed by jet mixers that combine cement and water in a single pass operation or the more precision batch mixers that mix by circulating in a large tank but only mix a limited volume at a time.' Although an acceptable slurry can be achieved in the jet mixer by an experienced operator, the batch mixer allows closer control in critical, small jobs. The jet mixers' are used for almost all large jobs that

require a constant supply of cement slurry at a high rate. The density of slurries mixed by these methods must be checked periodically with a pressurized mud balance to obtain consistent density. Density is important to control the reservoir pressure and prevent formation fracture breakdown. The quality of the water used to mix the cement varies widely depending upon the specifications required by the company involved. Fresh water, seawater and some brackish waters are used to mix cement slurries. For any source of water, the behavior of the resultant cement in terms of setting time and pumpability must be known before mixing. Pumpability is measured by a laboratory instrument called a con~istometerT.~h is device measures the setting time of a cement slurry by stirring the slurry (under pressure) until it thickens too much to stir. The output is as units of consistency, and is time related. This test yields the time that a particular slurry can be pumped at a given temperature. Because of the development of offshore fields, seawater has become very widely used for cementing. Seawater, like most inorganic salt brines, slightly accelerates the set time of cement. Fortunately, as

shown in Figure 3.3, the chemical composition of seawater throughout the world does not vary to a large degree,5 but some chemical additive additions may be necessary to control effects of salt and temperature. Use of brackish water (from bays, swamps, sewage or produced waters) can cause problems. High salt contents, especially calcium chloride, may decrease the cement set time. Organic contaminates (such as oil-base mud) may slow the cement set time, sometimes so severely that the slurry does not set.

Accelerators or retarders may be used in the cement to change the set time from a few minutes to many hours. A retarder is used in deep or very hot wells to prevent the set of the cement before the job is complete. Accelerators are used in shallow or cool wells to speed up the set of cement so less rig time is lost waiting on the cement to set. Values such as filtrate loss control and cement expansion can also be directly affected. Cement additives may be divided into two general classifications based on their reaction type; chemical and nonchemical. Nonchemical additives are usually materials which affect the cement by altering density or controlling fluid loss. Chemical additives modify the hydration

(water intake).

Cement Density

Controlling the cement slurry density is critical for placing a column of cement where the formation may be fractured by a heavy slurry or would allow the well to flow if the cement slurry was lighter than the pore pressure. For a lighter weight cement than the normal 15 to 16 Ib/gal, bentonite clay may be added to absorb water to yield a lighter cement with higher bound water volume. Ten to 12 Ib/gal cement density can be achieved in this manner. Grinding the cement to a very small size will also require more water to satisfy the high surface area and lighten the slurry to the 10 to 12 Ib/gal range. Ultra-light-weight cement^,^'^ using hollow ceramic or glass beads can reduce the overall weight of

the cement slurry to less than 9 Ibs per gallon. Even lower densities can be achieved by foaming the cement with a compressed gas such as nitrogen.&’’The foamed cements can create densities of 4 to 7 Ib/gal but require careful control of annulus surface pressures to avoid gas channels and voids. All these light weight cements, although strong enough to support the pipe, have less strength than the regular portland cement. Heavy weight materials are added to the cement to increase the cement density, usually to control the pressure in the formation during the pumping of the cement. Iron ore, barite (barium sulfate) and sand can create slurries to 25 Ibs/gal. Other methods of preparing heavyweight slurries include the use of dispersants which allow less water to be used in a cement and still maintain pumpability. A chart of cement density for various methods of density control is contained in Figure 3.4.

In some treatments where the light weight cements are not used either by preference, economics or for reasons of strength, stage tools can be used to control the pressures on a zone by running a multistage cement job. A staged job separates the cement job into small cement jobs that only support a portion of the total column and weight. The tools prevent the cement columns from contacting each other until set. An example of a cement stage tool is seen in Figure 3.5. The simplest tool uses a drillable plug to seal the pipe below the tool and to open a set of ports that allow the next cement stage to turn the corner and start up the annulus. Some tools are equipped with a seal device that prevents cement from falling down the annulus and ruining the job by creating channels or by exerting more pressure on the lower zones. With these tools, even a deep well with several zones can be cemented by turning the job into several consecutive jobs. The staged concept can also be done by cementing with a small volume and perforating the pipe above the last cement top and repeating the process. However, the tools save WOC time between jobs. The obvious drawback to the tools is the same for all downhole tools; reliability.

Fluid Loss

Lost circulation materials control the flow of whole cement into natural fractures or extremely large vugs. The control materials come in three basic types: granular, lamellated and fibrous. Granular materials such as sand and other products set a secondary matrix by filling cracks and vugs in the formation. They may have a size range from 1/4 in. diameter to fine powder to achieve control. Lamellated or flaked products such as shredded cellophane stopped at the formation face and create a blockage on which cement will form a filter cake. Fibrous material such as paper, nylon or polypropylene are best suited to bridge small fractures.

can be lost waiting on cement (WOC) to set. This WOC time can be shortened by the use of accelerators. Cement requires very little strength to physically support the casing. More strength is required in withstanding loading from drill bits and pressure. In designing the cementing operation, it is imperative that high strength cements be used around the casing shoe (the bottom end of the pipe) and across potential pay, thief zones (areas of fluid loss) and water producing zones. Filling the annulus behind pipe and zone separation requires very little strength and more economical cements or cement extenders may be used.

While the cement slurry is liquid, the hydrostatic force from the weight of the slurry exerts force to prevent entry of gas into the wellbore annulus. When pumping stops, the cement starts to gel and set and it begins to support itself by the initial bond to the formation. This initial attachment, coupled with fluid loss to the formation, reduces the applied hydrostatic 10ad.l~F luids can then enter the annulus, causing voids and channels in the cement behind the pipe. Methods of control include reaction with the formation gas to plug the channels14 and stopping the gas from entering by reducing ~ermeabi1ity.Ul~s e of an external inflatable casing packer (ECP) is also an option.16 This tool operates like a hydraulic set

packer between the casing and the open hole. The necessary volume of cement is the volume of the openhole less the volume of the casing across the zone. An excess of 30% to 100% of the total is usually added to the cement volume to allow for washouts and mud contaminations. The 30% to 100% range of excess cement volumes is large, even for the technology of the oil field. It reflects the variability of drillers expertise and formation conditions. Hole volume is calculated from the caliper log. The bit diameter should not be used for hole volume calculations since it will not reflect washouts. In most operations, 4-arm caliper tools that give two independent diameters are more accurate than 3-arm calipers that give a maximum or averaged reading.

Cementing Design

The first use of cement in the oil industry is recorded as a water shutoff attempt in 1903 in California.* At first, cement was hand mixed and run in a dump bailer to spot a plug. Pumping the cement down a well was soon recognized as a benefit and a forerunner of the modern two-plug method was first used in 191 0.2 The plugs were seen as a way to minimize mud contact with the cement. Although both mechanical and chemical improvements have been made in the cementing process, the original plug

concept is still valid. Cement design includes the selection of additives and equipment to remove mud and properly place and evaluate the cement. The cement design depends upon the purpose of the cementing operation. The initial cement is usually to fill the annular space between the casing and the hole from the casing shoe to the surface or a point several hundred feet above the zone that must be isolated. The first cement job is called primary cementing and its success is absolutely critical to the success of subsequent

well control and completion operations. When a primary cement job fails to completely isolate the section of interest, repair of the cement job must be done before drilling can proceed. These repair steps are covered by the collective label of squeeze cementing. In a squeeze job, cement is forced into the zone through perforations, ports in tools, hole produced by corrosion, or through the clearance between casing overlap liners or strings. Although squeeze cementing has become commonplace, it is expensive and its use can be curtailed through improved primary cementing procedures.

Primary Cementing

In primary cementing, the object is to place a continuous sheath or band of cement around the pipe which extends without channels or voids outward to the formation face. Primary cementing is not an easy operation to do correctly. Many things can happen during this process to create problems or weak spots in the primary cement design.

Application

The mixing of cement and water is the first critical area of application of cementing technology. To prevent fracturing or loss of control, the water and cement must be blended together at the proper slurry density. The weight of the slurry is equal to the weight of the set cement less any weight of free water. One of the first questions that should emerge in a design is the volume of cement needed for a job. In a short string or shallow string, complete cement fill of the annulus is needed, plus at least 30% excess to displace the lead cement that is in contact with the mud as the cement displaces the mud

from the annulus. Cement contaminated with mud will not form an effective seal; it may have mud channels through it and may not develop any strength. In cases where the mud has not been adequately conditioned before cementing, as much as 100% excess may be appropriate. The volume of the hole should be measured with a caliper after removing the drilling string and before running casing. Calipers may be available in 3-arm, 4-arm or multi-arm styles. Three-arm calipers report an average “round” hole diameter based on the smallest diameter reading of one of the arms. The four-arm calipers work as two 2-arm calipers. The data from this tool draws an average of the hole based on two circles or ellipses. Both tools are capable of underestimating the hole volume.

The caliper tools report the data on a log track that shows deviation from a theoretical line reflecting gage hole or bit size. Washouts and irregular hole volumes must be calculated to give an accurate reading on hole size. The easiest way to calculate hole volume in a washout is to use an average washout diameter equal to at least 90% of the maximum caliper measured diameter where the diameter is fluctuating widely and 100% of the maximum diameter where the hole diameter is more consistent. Calculating the volume of the hole in vertical segments of similar diameter yields usable results.

The problems in cementing through a washout are that fluid velocity becomes very low in a washout; swept debris at the leading edge of the cement drops out or mixes in and the cement slurry will no longer scour or clean the mud cake in the washout.

There are two types of oilfield cement mixing equipment: on-the-fly and batch. Batch mixing is done in a large tank with circulation or paddle mixers. The cement and the water are measured into the tank, sometimes with an on-the-fly mixer, with small additions of cement or water to get the right slurry density. Although batch mixing is by far the most accurate method, the size of the cement job is limited by the volume of the tank at hand. Mixing on-the-fly involves moving steady streams of cement and water through a zone of turbulence produced by high velocity flow, Figure 3.6. The cement slurry produced

in this manner is highly dependent on the experience and attention of the mixer operator. Numerous problems with variances in slurry weight have led to averaging “pods” or tanks, Figure 3.7, downstream of the on-the-fly mixer. To minimize the damage produced from lighter or heavier than designed slurries, most cementing service companies have density monitoring devices to report slurry density back to the mixer operator.

Incorrect cement density can cause gas migration, poor set strength, inadequate cement bond, blow outs, formation fracturing and lack of mud displacement. Cement slurry density must be rigorously controlled to enable the subsequent well completion steps to be carried out successfully. Once a consistent cement slurry blend has been achieved, the second critical area, that of the displacement step, begins. To effectively bond the pipe to the formation with cement, the drilling mud and the drilling mud filter cake must be completely removed. Failure to remove the cake or mud will lead to failure of the primary cement job by leaving mud channels in the cement. Failures necessitate squeeze cementing or repair operations. Mud conditioning and displacement are the next critical areas of cementing In order for cement to isolate zones, a sheath of cement must completely surround the pipe and bond the formation wall to the pipe. The mud cake must be removed and the pipe must be centralized. Centralization is needed to provide sufficient standoff or clearance between the casing and the borehole wall. Removal of the mud and mud cake is done by a combination of chemical and physical actions that are well documented but often overlooked during application. The ease of mud removal depends upon the physical condition of the mud and the access to the mud. Mud displacement begins with decreasing

the gel strength of mud and removing cuttings. After casing is run in the well, the annular space open to flow is smaller than when drill pipe was present. The smaller annular area creates higher velocities that can disturb deposits of cuttings. Cuttings can accumulate in the lead portion of the cement, contaminating the cement and creating blockages that can create lost circulation. The presence of a mud cake will prevent bonding of the cement to the formation. An estimation of the volume of cement needed for removal of mud cake by turbulent flow is:’

Studies have shown that a contact time (during pumping) of 10 minutes or longer provides better mud removal than shorter contact times.’ The equation is valid as long as all the fluid passes the point of interest. The equation will not be valid for mud outside the path of the flowing fluid, such as when the casing is uncentralized and is pressing against the formation. Movement of the pipe during cementing is one of the best methods of improving the mud displacement and reducing the number of mud channels remaining after ~ eme n t i n g . ’R~e~ci~pr~oc ation (up and down) and rotation of casing help force the mud from the pipe/formations contact areas and insure a more even distribution of cement. Rotation of the pipe requires special rotating heads to allow pumping while turning. Reciprocation, or moving the casing up and down a few feet while cementing, can be done more easily but does not force the mud from the contact area in the same manner as rotation. Addition of scrapers to the casing can help remove hard mud cake.24 Use of centralizers minimizes

contact area and may make pipe movement easier. Displacement of the mud and the mud cake cannot always be accomplished by flowing cement. Heavily gelled muds and tightly compressed filter cakes are very resistant to removal by any flowing fluid. Special removal procedures are necessary. The basic mud removal step is to pump the cement in turbulent flow: the combination of the high velocity, high viscosity and abrasive nature of cement

work in unison to scour the formation and casing. During scouring, much of the mud and cake materials are mixed in with the first cement pumped. This contaminated cement must be removed from the well. In the cement volume design, the allowance for contaminated cement is contained in part of the 30% to 100% excess cement normally designed into most jobs. If muds and mud cakes cannot be removed by cement flow, special preflush fluids and mechanical devices are available to improve displacement. To improve mud and mud cake displacement, the binding agent in the mud must be broken down. In most cases, the mud binders are clay, polymers or surfactants. Chemical flushes of acids, solvents, or surfactants are useful but must be selected for action on specific muds. These flushes are pumped ahead of the cement or spotted in the annulus before the cement job. Mechanical devices for mud and mud cake removal include casing centralizers, scratchers for cake removal and turbulence inducing devices to improve mud scratchers break up the mud cake during running of the casing. Complete removal of the cake is not necessary; the action of the cement will often be sufficient to remove the cake fragments once the integrity of the cake has been disrupted. The wire or wire rope The alignment of casing in the borehole is an often neglected factor that has a tremendous impact on mud conditioning, cementing, perforating, and production, particularly in highly deviated or horizontal hole^.^^-^' Uncentralized casing always lays on the low side of the hole. In soft formations, the casing

may even embed or bury into the wall of the formation. When casing contacts the wall, the drilling mud cake and some whole mud is trapped between the casing and the rock. This mud cannot be removed. Mud removal attempts by flushes and turbulent cement flow will have little contact as shown in the velocity profile sketches of Figure 3.8 and the photographs of mud displacement and channels created in a flow study recorded in Figure 3.9. Cement bypasses the mud and channels are left behind the pipe. These channels may completely undermine the principles of zone separation by cement and usually require repair by squeeze cementing. Channels are the most common form of primary cement

failure. Centralizers and pipe movement can improve the wall of the hole so that cement may more evenly displace the mud and completely fill the annulus. The design of centralizers varies widely with the application. Centralizing casing in nearly straight

holes is relatively easy, but as holes become more deviated, centralization becomes more difficult. In the more deviated wells, the weight of the casing will flatten most spring centralizers and may deeply embed some of the solid fin body units. The actual number of centralizers needed for a well depends on the acceptable deflection of the pipe and the severity of dog legs in the well. Examples of centralizers and their spacing are shown in Figure 3.10. Note in the examples that the centralizer spacing

decreases (more centralizers needed) as hole angle, pipe size and clearance increase.'^^^ The spacing is usually calculated by computer using a model such as that of Lee et al.27 These programs project spacing on the input of depth, dogleg severity, lateral load, tension and deviation. Typical spacing is from 30 to 60 ft between centralizers.

The variance in casing weight can be illustrated by the following examples of buoyed weight of casing.

Mud retards (slows) the set of cement. Minimizing this effect requires mud removal and separation from the cement whenever possible. Most casing strings are run full of mud during casing placement for assistance in well control. Cement displaces the mud from the casing before it flows up the annulus. If the mud is lighter than the cement or the mud has high gel strength, the cement will tend to finger or channel through the mud during its trip down the casing, mixing cement with mud. Mixing of mud and cement in the tubulars can be prevented by use of the two plug system. Before the cement is circulated down the well, a hollow rubber plug (Figure 3.11), with a disk that can be ruptured at high

pressure, is placed in front of the cement. The cement pushes this plug down to the bottom of the well, wiping the inside of the casing and displacing the mud from inside the casing ahead of the cement. At the bottom of the well, the plug “lands’t or is “bumped” and pressure builds up, rupturing the disk. Cement comes through the plug and can “turn” up the annulus. The second plug is dropped at the end of the calculated cement volume and the cement is displaced down the well with mud or water. The second plug, or top plug, is solid and has the same set of wipers as the first plug. At the bottom of the

hole, the top plug reaches the top of the first plug and pressure rises, indicating that the plug has been “bumped.” The plugs are made of drillable material that can be easily removed if the well is deepened. Correct loading of the plugs is critical. If the plug sequence is accidentally reversed and the top plug is dropped first, the job will “end when this solid plug hits bottom and the casing is left filled with cement. The actual displacement in the wellbore is very much different than the surface pump rate might indicate, especially when the density of the mud is much less than the density of the cement.*’ When a

lighter mud is displaced, the cement is in a “free fall.” The cement density is enough to rapidly push

the mud ahead and displace it from the well without the driving pressure of the pump. This is most noticeable in the later stages of the job during displacement when the casing contains more mud than cement. Surface pressure can go to almost zero at low injection rates (the well is said to go on ‘‘vacuum”). At this point, the well is taking fluid faster than it is being injected and mud return rate from the well can be more than the cement injection rate (a vacuum, with void space, is being created in the casing at the surface). As the cement turns the corner at the bottom of the well and starts up the annulus, the injection pressures caused by the heavier cement density will climb. The well returns, which

are monitored continuously at the surface, may go to zero as the cement fills the void volume in the pipe that was evacuated during free fall. It may appear that the well has lost returns by breaking down (fracturing) the formation. This rapid movement of fluids must be included in the design to allow control of the mud. The problems involved with free fall are rapidly increasing bottomhole pressure caused by resistance to faster than design mud flow rates around the shoe and an apparent “loss of eturns,” as the cement fills the voids created during the initial free fall. An example of a field job showing

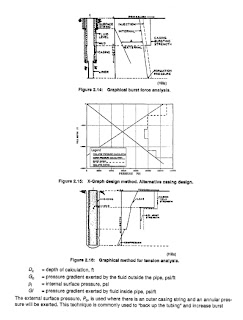

pump and return rates is shown in Figure 3.12.29 If, for example, the low rate of returns after 2 hrs, caused the operator to reduce the injection rate in an attempt to limit the apparent “loss” of cement, the cement would not be in turbulent flow and the mud cake might not be cleaned off the formation.16

After the plug has been bumped, the waiting-on-cement time, WOC, begins and pressure is held until cement has set. Pressure control is assisted by the float equipment. These devices are flapper or poppet valves near the bottom of the string that prevent the cement from returning to the casing. The oneway valves are of drillable material and are designed to stand the high velocity flow of large quantities of abrasive cement without damaging the sealing mechanism. Examples of the float valve are shown in Figure 3.13. If the float is at the end of the casing string, it is called float shoe. If it is placed a joint or two off bottom, then it is called a float collar. The preferred location will depend upon the operator

but for reasons of cement contamination control, float collars are usually preferred. The float collar results in a joint or two above the shoe being filled with the last cement pumped. This last cement may be contaminated with residual mud scraped from the casing wall by the top plug. Use of both a float collar and a float shoe are accepted practice in some areas. The dual floats are used as an extra barrier against pressure leak back. After WOC, drill bit just smaller than the casing id is then run if the well is to be deepened. The hole is drilled through the casing shoe and into the formation beneath this string. At this point, the casing

shoe is generally tested to insure that a good, leak-tight cement job has been obtained. If there are

leaks during this pressure test, the well is squeezed with cement until a pressure tight seal can be obtained. Since the casing shoe is the weak spot for blowout control, this step is a necessity. In summary, to properly place a good primary cement job requires several factors: selection of the right cement blend, the conditioning of mud, the removal of mud cake, centralization and movement of the pipe to insure full cement contact around the perimeter of the outside casing wall and use of enough cement to isolate the full zone.